Entrepreneurial Archetypes

There are several different archetypes of tech entrepreneurs. I've noticed some of these traits in myself and many other people who have built companies. I have opinions about which archetypes have a higher likelihood of achieving success, but all of them seem to work. There are also a lot of entrepreneurs who have characteristics of multiple of these archetypes and live at their various intersections. I've attempted to group them into five categories (but I'm sure there are plenty more): the serial inventor, the opportunist, the problem obsessor, the industry expert, and the academic.

The Serial Inventor is clinically addicted to building things. For some ADD can be a hindrance. For the serial inventor it’s a superpower. This entrepreneur believes that everything they encounter in the world can be done better. This drives them absolutely insane to the point where they need to constantly be hacking away at these problems. There is no off button for their capacity to generate ideas and actualize them. This person is usually inspiring to be around. You may use the word Genius to describe them, and their ability to go broad is remarkable.

The Opportunist is someone who sees a hole in a market and goes for it. I've seen a lot of Associates at VC firms fit into this category. This is a person who evaluates and maps markets, knows all about TAM, studies industry trends, and when the timing is right and they develop the guts, they pounce. The Samwer Brothers from Rocket Internet are a quintessential example of this, studying companies that work in the US and bringing them to Europe. Non-industry specific venture studios also can be grouped into the archetype. I don't use the word "Opportunist" pejoratively - entrepreneurship is all about seeing opportunity and chasing it.

The Problem Obsessor is the entrepreneur that is absolutely obsessed with a singular problem. Sometimes it's hyper-specific like "why can't we do reply all over SMS?" and other times it might be super broad like "too many people die of heart disease." A lot of times this person is a generalist. They experience a problem firsthand and then they become fervently passionate about solving it. Sometimes they only want to solve it for themselves but their solution catches fire. I love this approach because it scratches a very personal itch.

The Industry Expert is the entrepreneur who has a very unique insight into how something should work in a relatively niche environment, but believes that insight/solution may be more broadly applicable with big-business viability. These are the people who may have been working in a corner of information security or specialized databases for many years and believe they can invent something novel and important in that space. We see this a lot in enterprise, but it can be applicable anywhere. They're steeped in an industry, have a competitive advantage in the knowledge and network they've accumulated, and they're ready to leave their mark.

The Academic is the entrepreneur who finally decides that their research, scientific knowledge or invention is ready for commercialization and they're the one to do it. Sometimes it happens by accident. Sometimes a business person (maybe an Opportunist?) gives them the nudge. Sometimes they're just ready to rock. They're super technical and have world-class depth in an area, and translate that knowledge into something groundbreaking.

I've been a couple of these. GroupMe was a very personal problem. We wanted to build reply-all SMS for our friends so we could stay in touch before, during and after music festivals. Then we realized we were building a close-ties network and just built features that made our experiences with our groups more fun. If I am being honest with myself Fundera was more of an Opportunist approach. I was inspired by companies like Lending Club and Funding Circle in 2013 and innovations in lending, and believed there was a unique moment-in-time opportunity to create a dominant platform in the US for SMB lending. I tried to convince myself that it was all about "empowering entrepreneurs." A piece of it definitely was. But truthfully I mainly just wanted to build a great business. It's taken me a while to admit this to myself and be totally comfortable with it.

One of the things I've been grappling with is an entrepreneur's "interest longevity." Regardless of archetype, interest in a product / business / idea / industry likely doesn't last forever. I don't think I could have done GroupMe for a decade and still been as passionate about the problem, and my enthusiasm for the world of SMB lending meaningfully waned towards the end of my Fundera journey. If you talk to any Problem Obsessor, Opportunist or Generalist who has built a company, they will almost always declaratively say they'll never build another company in that industry again. I do wonder if one archetype is inherently more obsessive for longer durations, and I have immense respect for and bewilderment of entrepreneurs who remain passionate about their singular company or space for decades. It's a superpower that I'm glad I don't have. Mixing it up is fun for me.

Another observation is that it's really neat when entrepreneurs from different archetypes partner with one another to start companies, and when executives who resemble these archetypes join companies. The differences in respective characteristics and motivations feed off each other for the better and ultimately create a winning environment for success. Different archetypes bring different energy and raison d'etre to the table, and that makes everything more fun.

A Cliché, Not a Snowflake

I've come to the conclusion that after their first or second exit, almost every entrepreneur goes through an identical existential crisis and thought process around what to do next with their life. I can confidently say this because I'm going through it right now and as part of my process I've talked to a lot of different entrepreneurs who have experienced something similar.

The process looks something like this:

-After having spent nearly a decade building companies, you finally have the opportunity to lift your head up and see the world at large. There are many different problems that need solving, and a lot of exciting things happening beyond the myopic thing you maniacally focused on for the past ten years. Also, holy shit! While you've been heads down it feels like the world has passed you by. Things have changed! It's time to catch up.

-You begin your journey of reflection and start to recognize a couple different things:

Wow, it would be really great and smart to have a lot more diversification in your portfolio instead of one giant egg. Is there a construct that enables you to do this?

Maybe I should be somewhere between more thoughtful to super thoughtful about the idea I want to pursue next. That will probably produce a better outcome!

Do I really want to commit another decade+ to one single thing again? Do I still have the energy to do this?

-You start to evaluate alternatives to being an entrepreneur. The most obvious one is VC. You're cut out for the job because you've built companies. You also think it might be easier than building a company. You will probably work super hard because you care about being great, but you won't suffer nearly the same stress. Also, you can make a lot of money. And if you're not a shitty person, which you probably don't think you are, you genuinely believe entrepreneurs will like and want to work with you. Maybe you become a VC, but you also want to know if there are other configurations that might work for you.

-Instead of abandoning building things, you come up with the amazing idea that every other entrepreneur has thought of before and decide that instead of building one company at a time you want to build 10 at a time! It's time for a venture studio / incubator! I want to be just like Kevin Ryan and the people at Sutter Hill. If Atomic figured it out so can I! I don't just have to put all my eggs in one basket, I can have many baskets simultaneously!

-Wait! Another alternative to this is just building a Hold Co. Have you seen IAC? Maybe we can buy companies and make them better in addition or as a substitute to just building companies. Have you heard of Tiny? Do you listen to podcasts featuring "business experts" who are building these Hold Cos? OMG have you heard of Constellation Software? Holy shit, LFG!!!!!

-Eh, that was a close call. I almost bought an HVAC company.

-Where do I start? Hunting for ideas feels really icky and disingenuous. When I used to build stuff I did it because I was passionate about the thing. I cared about solving a problem. I didn't just map out markets and analyze companies and say, "There's a gap there! It's time to build!" I want to feel that fervor again. Why don't I feel it? Am I too old? Did I lose my edge?

-I'll just eat some psychedelics and then the answers will come to me. Ugh, no answers yet. Maybe I'll eat some more!

-Okay, I know the Meaning of Life now but I still have no idea WTF to do with mine.

-Now what...

-I guess one day at a time and one foot in front of the other. I believe something will inevitably inescapably call to me and the momentum will snowball. Just need to optimize for luck and serendipity in the interim. Finally at peace. Let's see where it goes...

-Step 3: Profit

And that, my friends, is the cliche, tried and tested journey that insane people embark upon when venturing once again into the unknown.

The Rule of 45

I've spent the past several months decompressing and occasionally thinking about what to do next, or more accurately, thinking about how to think about what to do next. One of the things I keep coming back to is a conversation I had with Nigel Morris (one of the kindest, sharpest, and most affable entrepreneurs out there) last year. He shared a framework that really resonated for me: Spend the first third of your professional life/career (ie ~15 years) building a network and becoming an expert in something. Use the middle third for capitalizing on and leveraging the knowledge and skills you've accumulated. And the final chapter can be spent paying it forward.

I like this because it's a simple way to think about things and also provides a framework for asking some important questions: What are you actually good at? What does a career or profession mean to you? For the middle third, to what end(s) do you wish to capitalize or leverage the foundation you've built? It's a tough series of questions to answer, and they usually beget more questions than answers, but it's been a fun and insightful journey for me to try to tackle them.

One of the things I'm grappling with is that I dislike the word career. Perhaps the concept is offensive to me because I don't like thinking about a strong dichotomy between "work" and "personal" life. It's also challenging to think about what else you can do with a history of entrepreneurship other than build more companies or do some form of venture to help other entrepreneurs. Regardless, this way of breaking things down into three ~15-year intervals (or The Rule of 45) is a forcing function to ask some of the right questions when reflecting on the past and evaluating the future.

AI(ngst)

Watching the world of technology evolve at its fastest rate ever due to AI hitting its stride is absolutely nerve wracking. As an entrepreneur focused on software, I feel like I'm experiencing an existential crisis. I imagine most founders are going through something similar. It's anxiety inducing. We are grappling with unanswerable questions right now: What is the future of software? Will what I'm working on be made obsolete by AI over the next 12 months? 24 months? 5 years? What does it mean if the rate of progress and change continues to accelerate? What The Fuck?

Most people building things have been living in a relatively safe world. Tyler Cowen hits the nail on the head when he proclaims, "Virtually all of us have been living in a bubble 'outside of history.'" Technology entrepreneurs have certainly experienced a lot of change in the past two decades with the transition to cloud and mobile, but those moments felt much more understandable. Sure, there were plenty of surprises and disruption, but nothing even remotely comparable to the seemingly inevitable radical AI upending that is upon us.

It's a moment in time where we experience equal parts excitement about what is possible and absolute dread at the thought that everything we know how to do and excel at feels like its growing increasingly irrelevant by the day. I am immensely grateful that Fundera was acquired two years ago and I'm a free agent that gets to soak this all in and think deeply (although it's unclear what good the deep thinking will actually do). I do not envy founders who are many years into company building and need to grapple with the existential questions this moment in time requires. I have a great deal of empathy for you.

It's difficult to make predictions in times like these. It seems as if even the best builders will be subject to significantly more volatility and randomness when it comes to their success. And the bar was already dauntingly high. One thing I believe to be true is that this new world will put a premium on people who deeply focus on problem-solving instead of opportunism. The past decade has been riddled with people searching for arbitrages in software, and I think AI will likely drive the returns of that approach close to zero. Dedication to solving a problem (even if it's coupled with opportunism) will pay dividends. Primarily because it gives you a more profound reason to wake up motivated in the morning and the willpower to battle through what will certainly be the most insanely volatile decade in technology in history.

Advice and Context

Advice is a tricky thing. We get it all the time. We give it all the time. And we seldom know if what we are giving or getting is actually any good until we evaluate it in hindsight. As an entrepreneur, I've spent a lot of time speaking with mentors, advisors, peers, and friends asking for advice, listening to their stories about what they've done over course of their careers and how they've handled certain situations. As an investor, I spend a lot of time sharing my own stories and advice with other entrepreneurs.

Whenever giving advice, I like to provide a disclaimer that whatever I'm saying is strictly informed by my own set of unique experiences, and that the context in which I learned whatever I'm sharing is important. When receiving advice, I think this is a crucial thing to internalize: not everything you hear, even if it's from a person you genuinely admire and trust, may be relevant to your situation. Understanding the context in which they learned a lesson is key in applying that knowledge to your own set of circumstances.

When receiving advice, it's important to be very wary of people who declaratively state, "You MUST do this!" Unless someone is sharing something that is objectively true, like 2 + 2 = 4, then you must push to understand the context of their experience. The other exception is when someone's advice is an oft cited cliche. I've found that most advice-oriented cliches are usually truisms - they're tropes that have been learned and repeated over and over again (e.g. "Hire slow, fire fast").

I like to think of advice as little kernels of knowledge I accumulate over time that I can draw on whenever I feel it's applicable to a certain situation. Collecting these data points and refining how to apply them over time is a unique skill in and of itself. But, as the cliche goes, context is key.

The Disaggregation of Search

For the first time in decades, the way we search for things on the internet is being disrupted. Google, which by every measure is the world's leader in search, has built a remarkable business surfacing information when we have questions. But a series of new innovations, namely ChatGPT and LLMs, coupled with new frontiers in search UI (e.g. chat-based search), are going to rapidly transform how we get the information, and hopefully knowledge, we seek over the coming decade.

I once read that the history (and future) of business is just an endless cycle of aggregation and disaggregation. I went to Google to figure out where this theory came from and the results I got back were not helpful. So I went to ChatGPT and found exactly what I was looking for:

Before Google the way we found information on the internet was by combing through verticalized directories that were compiled by humans working for companies like Yahoo and MSN. Google, through an innovative approach to programmatically and algorithmically indexing the web that yielded results far superior to any other search engine, aggregated the entirety of search such that we only had to go to one place to get the information we needed. Goodbye, directories. Hello, one search bar to rule them all. We've seen its evolution over the past two decades and it has had a profoundly positive impact on the world.

Today, it is hyperbolic to say that search is broken. But it is an understatement to say that it could be better. The amount of information available on the internet has grown by many orders of magnitude since Google's inception, and the way in which we interact with information (i.e. through web and mobile applications) has changed dramatically. It has become impossible for a single search aggregator to answer all of our questions in a systematically excellent and satisfying way.

Over the past several months, a new suite of tools (e.g. ChatGPT and LLMs) and experiences (e.g. chat-based search) have been introduced to hundreds of millions of people across the globe. These are the beginnings of the infrastructure that will power the disaggregation of search. Jim Barksdale once famously stated: "there are only two ways to make money in business: One is to bundle; the other is unbundle.” It is my belief that search is going to be unbundled over the upcoming decade (and then ultimately re-bundled when AGI can satisfy all of our search desires in a uniquely personalized way, but that's for another (several?) decades). And it's going to happen by entrepreneurs building on the aforementioned tools to target underserved and overlooked customer segments that Google cannot prioritize satisfying.

The defining characteristics of these search dis-aggregators are that they will be differentiated from conventional search in UX (e.g. chat-based and other novel approaches), vertical or use-case specific to improve the thoroughness of answers, and powered by LLMs that uniquely improve as usage grows. The tools are finally here to create search and information-finding experiences that are 10x better than what Google can do across a wide variety of verticals. We are beginning to see it with companies like Consensus and Phind and several more highlighted in these good pieces by Connie Chan and Justine Moore at a16z and Talia Goldberg at Bessemer.

I have spent the better part of the past decade building businesses that used Google and SEO as their primary customer acquisition channel. If I were to build something new I'd focus on creating a 10x better experience than Google can for a specific vertical or use case and relentlessly work to establish it as the most trusted brand for providing the right information in a compelling way within our area of expertise. It's an exciting time to unbundle your bit of search.

2023 Goals

Last year I publicly shared my goals for 2022. I like having a public record of this. Diving in, here's how I stacked up against my goals from last year. I am really happy with my achievement rate. If these were OKRs I'd consider it a successful year.

I like a tops-down approach for personal goal setting, beginning with answering the question: "If I were 80 years old, what would I regret / not regret having done over the course of my life?" From there I like to list out my ten-year goals at a very high-level, and then dig into annual goals.

This year I have updated my regret minimization framework:

By the time I'm 80 years old, I won't regret having spent an abundance of quality time with my family, having read and retained the learnings of terrific books and being knowledgeable about the world (both the way things work and why they work that way), knowing myself and what makes me truly happy, having traveled and explored the world to my heart’s liking, spending time in nature, feeling like I’ve made people’s lives better and contributed to civilizational progress through my professional endeavors, and investing in the relationships that matter most with friends and family.

I've also updated my long-term (10 year time horizon) goals. I really like how these are simple and more about the way I will feel in ten years instead of objective numerical measures of success.

And finally, I modified my goals for 2023. These aren't a major departure from 2022, they're really more of a continuation of what has been. I think it's good that these are iterative and evolutionary - it makes them feel doable and realistic and hopefully will enable the progress to compound over a ten year period.

Here's to a fun and meaningful 2023!

Uncertainty

Today is my official last day at Fundera / Nerdwallet.

For the first time in my life, I have absolutely no clue what will come next. This is a new experience for me and it fills me with anxiety. But I am eager to learn how to explore and embrace the uncertainty.

When I was a teenager I played tennis competitively. I was a nutcase and would regularly throw tantrums and break rackets when I lost. I saw a sports psychologist and he told me about an ancient Chinese phrase called wu wei which he described as meaning "go with the flow." While it's a minor perversion of this Taoist concept, Westerners have adopted it to represent an orientation of "effortless action," "non-doing," or "action through inaction." I love it and it has served me well.

As a Type-A-Control-Freak-INTJ, wu wei doesn't always come naturally, but when it does it's beautiful. I am ready to go with the flow.

When in Roam

Every once in a while I interact with a new product and have an epiphany: "Ah! This is it. This is the future and how the world will work."

Over the summer I caught up with one of my favorite entrepreneurs, Howard Lerman, and he said he had something to show me. It was a new product he and a bunch of colleagues from the various companies he had previously founded were building. He gave me a high-level overview of what they were doing, but showing always beats telling. And when Howard demoed Ro.am, I knew that I was witnessing what the future of work looked like for companies that operate out of an office, remotely, or a combination of the two. There has already been a lot of good coverage of Roam and I encourage you the check it out: Howard's remarks, CNBC, TechCrunch, Squawk Box, and IVP.

Many companies are trying to find ways for people to work better together remotely by creating some version of a browser-based HQ. We've seen everything from Meta's futuristic avatar-based version of the workplace metaverse to various permutations of gamified work experiences. Most of them come across cartoonish and impractical. But Roam actually feels like a HQ, but in the cloud. It's a viable virtual office.

I fell in love with it for several personal reasons. First and foremost, it mimics a physical office. I can see who is present, who they're meeting with, "knock" on their "doors," and have spontaneous conversations. It's the only thing I've seen that comes close to the in person experience. It's intentionally skeuomorphic, or as Howard describes, a "breakthrough office graphical interface," the same way Apple designed for the iPhone when they were acclimating the world to transitioning from desktop to mobile.

I need to be around people in order to feel energized, productive, and happy. If I ever were to build another company, I'd want to work from home 1-2 days per week and be in an office surrounded by people 3-4 days per week. Roam is the tool that creates a seamless experience transitioning through these modalities, ensuring nobody loses out on the magic of collaboration. It also eliminates roughly 50% of Zoom meeting time by making quick hallway conversations practical - the average meeting time in Roam is ~8 minutes!

The shift to distributed teams, remote work, and an asynchronous cadence has been confusing and hard for most founders and leaders. There's always a creeping suspicion in the back of your mind that people are phoning it in and that you're losing the magical moments that make building things so special and rewarding. And for those who value a performance based culture, the transition to remote or hybrid is a steep learning curve with few best practices. Roam is a happy equilibrium. It's the solution we've been waiting for that needs to exist. It's not that Roam enables managers to surveil, it's that it creates a work setting that enables people to flourish regardless of where they are. Some people and roles will always be able to operate asynchronously and that's great. But that's the exception, not the rule. And Roam empowers different configurations to embrace best practices and develop new ones for a rapidly changing work world.

I believe that Roam will be the platform that enables more magic moments between colleagues and helps us to do even better work together. I'm lucky to be an investor backing Howard and the incredible Roam team. Sign your company up here.

Vision vs. Research

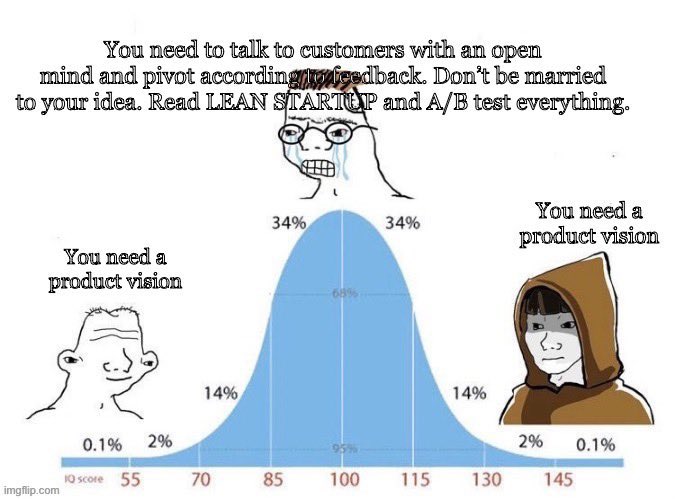

This weekend this tweet appeared in my timeline and it deeply resonated with me:

Over the past several years I have noticed a trend that people are starting companies for the sake of starting companies. I am a big proponent of entrepreneurship and believe it is a very positive thing for more people to feel empowered to start companies. It's how we make more progress faster. But I do not think it's a good thing to be a founder simply for the sake of being a founder. And this tweet characterizes how most people who fall into that bucket go about it. Because the gravity of wanting to start something is so strong, people do tons of research across a variety of different problem spaces until they land on something they think may have potential. And they do this without a deep passion and vision for the problem they are trying to solve.

I think this is a sub-optimal and time-wasting path of entrepreneurship. In my experience, the best founders start with a bold vision of how something in the world should work and what the end-state of the problem they are trying to solve looks like. They have a strong product vision and relentlessly pursue it. They are obstinate about what success looks like, but pragmatic enough to know that they may need to modify the course of their journey in order to succeed. Stubborn about vision, strongly opinionated about where to start, and flexible enough to make modifications once learnings are accumulated.

Loading up on research and constantly pivoting based on feedback before taking a first step can be a negative indication that a founder lacks conviction. And it also deprives founding teams of developing the most important muscle they need when getting something from zero to one and beyond: shipping things. Talking to potential customers is important, but shipping is better. Sometimes you need to will something into existence, and there's zero substitute for a strong vision coupled with the ability to ship. No amount of customer research can compensate for a lack of this.

This doesn't just apply to the earliest stages. In companies that have reached product market fit, I have seen customer research become a substitute for vision + shipping. It leads to inertia. Again, research is important, but if you truly have conviction about something, the best way to test it is to build it. There's no right way to build a company, but I have a strong bias towards doing the things that will generate the momentum you need to accomplish ambitious goals.

981

981