Programmable Anythings and Headless Applications

One of my favorite places to hang out in Warpcast is the chess channel. There are a lot of people talking about current events in chess and posting tactics for others to solve. People will respond to the tactics by writing out their answers move by move in a new cast. Usually, the first person who responds correctly will be awarded $degen for their efforts. It's a lot of fun.

I thought it would be even more fun if you could interact with tactics in a Farcaster feed. Frames are the perfect way to experiment with making this happen. I think of Frames as interactive applications that can be embedded into a Farcaster feed and usable in any FC client. The first Frames have been relatively simple, but it doesn't require a stretch of the imagination to see how these can evolve into full-blown games and social interactive experiences over time. They are very reminiscent of Zynga's Farmville infiltrating Facebook years ago.

I wanted to create a Frame where you could solve tactics within it instead of having to post a picture in a cast, reply with answers, and wait to hear if you were correct. These types of web applications exist (chess.com has a great tactic application), but why not make it an experience inside the chess channel feed? I created a bounty on bountycaster and a caster responded to it with a quick and dirty version of a Frame. We worked together over a couple of days to refine the experience, and ultimately got to a good place.

While it's not perfect, my goal was to make something that was fun for people who like chess on FC to use, and to hopefully inspire people to push the envelope of what Frames can do. Can we build real interactive games inside them? Can they be social or multi-player experiences? When can I play chess against another FC user in a separate client but an audience could follow along in real time in a Frame? Are these ideas even possible?

This was a fun experience for me because it helped push my thinking around two areas. The first is the idea of Frames as interactive applications, or "programmable anythings" as I call them in my head. We are really at the very beginning of what is possible here. I haven't seen many instantiations of Frames that have actual inputs other than pressing a button. The Frame we created through this bounty has a text prompt, but there will inevitably be other modes of interaction within them over time. The skeuomorphic expression of this is Farmville in the FC feed, but something weird and native to the onchain experience will emerge and be very special, and it will happen after a lot more collective experimentation.

The second area is around the future of headless applications. When I created a bounty on bountycaster, I did not use a bountycaster client. Everything was done entirely within the Warpcast feed. I simply crafted an initial post, someone responded, and a job spec was fulfilled.

This experience reminded me of a post I wrote about agent native applications. The premise is that in the near future, agents will act on our behalf and existing marketplaces or services that require your eyeballs to visit their website or specific client will not be compatible with them for a whole host of reasons, but headless ones will and they'll emerge to fill this need. These headless applications are already emerging onchain. Sometimes they are referred to as headless marketplaces. Using them is pretty magical and the implications are profound when we think about the future architecture of internet services and marketplaces.

Bountycaster is an example of a headless application that has emerged in the FC ecosystem. You can think of it like Fiverr or Upwork, but instead of having to do everything through a specific website, I can initiate or fulfill a job request from anywhere within Farcaster. This means that as a job-doer my reputation is not tied to Fiverr or Upwork. It's portable across any onchain application and I can bring it with me. And when I want some work to be done, in this example the creation of my chess tactics Frame, I can post it anywhere onchain and it can be distributed and responded-to through any client built on FC. Being headless enables a job post to proliferate and be accessed everywhere onchain, and any job-doer now has a portable and self-owned profile, work history, and reputation. This is an architecture that is also compatible with an AI agent-centric future. I invested in an iteration of this Bounty concept years ago with a project called Ahoy, but bountycaster pushes this several steps further into the future.

There are some obvious holes I encountered in the bountycaster experience, but those will all be patched (eg escrowing payment at the outset of a job and having a network of arbiters that can subjectively determine when a bounty has been fulfilled to spec). The whole process felt familiar but entirely novel. It was a taste of things to come in the future and yet another reason to be excited about the pace of rapid experimentation onchain that's creating fun and useful consumer experiences in entirely new ways.

Social Media Onchain

Social media platforms have evolved in a variety of different ways. Some are about sharing things with friends, and many of them have become a way for creators to put content into the world to entertain an audience. It very much feels like the dominant platforms today have become sterile. We use them, but they’re not fulfilling, nor do they have the pioneering sense of adventure and wonder they did as they emerged many years ago.

Recently I wrote about how something magical is happening onchain in consumer social. The Warpcast community feels like the early days of Twitter, and the openness of Farcaster has made the feed an experimental playground similar to early Facebook when third-party apps like Zynga could build companies on top of the FB social graph.

There’s an emergent playbook for building consumer social apps in web3. It begins with a skeuomorphic version of the web2 counterpart that the crypto community embraces. People onchain have a real willingness to experiment with new things, so acquiring early users is much easier in web3 right now than it is or was in web2. During this first phase, it’s important for application developers to hone in on what makes their product uniquely differentiated from their offchain comp. What are some of the defining characteristics that are only possible onchain, and how will that create preference amongst users so it can cross the chasm to a non-crypto audience? Here are some early and obvious ideas:

Applications that enable creators to monetize have the ability to offer meaningfully lower costs. This is the “your margin is my opportunity” play. Why pay Patreon a high rake when you can use Hypersub? Why Substack when you can use Paragraph which is 50% cheaper? Less extractive fees will create economic preference amongst creators, and these savings can be reinvested in their art and livelihood.

Financialization is a major feature of crypto. With onchain social media, creators can do things like allow their audience to benefit and participate in a creator’s growth and upside economically. That’s something that has never existed before and a real incentive for fans to help creators expand their audience and flourish.

We talk a lot about the ability to own your audience and bring it with you wherever you go. This is one of the pillar features of web3. Farcaster cannot shut down your account the way Elon Musk can. Your audience belongs to you which means that you can distribute an infinite variety of content to them through a multitude of different applications and interfaces.

Open data and composability enable a lot of experimental things to happen in crypto. Usually when someone shares media to a platform, it stays within the confines of that platform. It’s hard for it to proliferate across the internet and make its way into a variety of different applications. The only place this really happens in web2 is when a publisher embeds a tweet, instagram, or video. In web3, an atomic piece of media or data can be reshared across any onchain platform, and a creator can and will consistently be compensated for its distribution regardless of where it was originally posted. Because media is tied to your identity instead of a specific platform, it can live in many different places simultaneously, wherever you choose to go. That is immensely powerful.

There are still plenty of hurdles to deliver a UX that will draw in an offchain user base. Current onchain social applications are too insidery. Connecting crypto wallets is not something the average internet user understands. Paying with tokens is not a widespread behavior. These things will need to ultimately be abstracted away from UX in order to onboard billions of people. Fortunately, many tools that help solve these issues are being developed and adopted.

Ultimately, users go where their friends and content creators are, and creators go to pockets of the internet where they can get distribution. Right now, given the lack of a scaled onchain social network, robust distribution is a missing link for offchain creators looking to make the migration. Perhaps the rapid experimentation and composable nature of onchain consumer applications will help to solve this problem. We may very well find that sooner rather than later web3 offers a much richer distribution opportunity across a variety of different networks and platforms, and there’s an argument that it’s easier to be early to a network and build an audience as opposed to arriving late to the party. It seems that the right approach is not to try to convince web2’s biggest creators to drink the kool-aid, but to make sure that the onchain gravity is so strong that tomorrow’s biggest creators emerge on web3.

Web3 Social: Skeuomorphic, Then Not

For a long time, the web3 ecosystem had to organize and communicate on web2 platforms. From the memes of crypto twitter to the project-specific communities that congregated in Discord and Telegram, there were no dominant web3 platforms. That is changing quickly and there is something special happening in web3 social right now.

Over the past several years, we have seen a series of new projects emerge that finally give the web3 community a place of their own. They are unique, constantly evolving, and growing quickly. These projects have real tailwinds because people who like crypto have an explicit preference to use crypto-native products instead of web2 ones (even if they are less convenient to use), they are willing to experiment with and try new things, and nascent communities are always more fun than big ones with a lot of noise.

The trend for a lot of these projects is that they begin as a skeuomorphic representation of their web2 counterparts to attract an initial audience, and then they rapidly experiment to introduce weird and crypto-native features. This is just the beginning of what we are seeing:

Twitter ➡ Warpcast

Reddit ➡ Warpcast Channels

Tumblr/Instagram ➡ Zora

Substack/WP ➡ Paragraph

Discord ➡ Towns

Patreon ➡ Fabric

TikTok ➡ Drakula

I’m sure there are plenty of other examples I am missing here. In all of these instances, the web3 version initially mirrors the web2 counterpart, but then they quickly diverge. A lot of times this divergence is marked by some crypto-native feature: financialization and minting as a web3 version of “liking,” things that can only happen because of web3 composability like Frames, the emergence of memetic tokens that transcend applications like DEGEN, etc. All of these things are new, they are weird, and they are uniquely web3. The other characteristic they share is they are simply more fun and entertaining than anything that exists in web2.

We are now beyond the hand-wavey language and posturing and pounding the table on “everything needs to be open and portable and LOUD NOISES” We are seeing applications emerge that are fun, have real DAU and utility, are birthing products and memes that transcend beyond those communities, and represent the beginning of a new wave of emergent social networks that are fundamentally different. And while it’s still early (when will it not be“early?”), things feel more promising, useful, and engaging than they ever have.

At the very least, it’s a joy to see so many people rapidly experimenting together, building new products and features that could have never existed before, trying new things, and having a good time. It’s very reminiscent of early Twitter where an early community of curious people took a platform and morphed it to their liking. Now it gets to happen all over again, just with a new set of tools, functionality, and a permissionless and open system to ensure its future belongs to everyone.

Use of Proceeds

One of the most important skills founders must hone is their ability to tell a compelling story. Part of that story, if they plan or want to use venture capital as a tool to grow, is articulating how much money they want to raise and what they plan to do with that money.

When raising capital, it amazes me how many founders will say something along the lines of, “Well, right now the market for Series A companies is $X, so that’s what we want to raise.” I find that type of finger-in-the-wind talk extremely lame and weak. It means that you haven’t taken the time to truly think about what your goals are - e.g., growth objectives, what you need to learn, build, and prove, and what resources you need to accomplish those things - and the capital requirements to get them done.

One of the things my investors taught me is that entrepreneurs need to be good stewards of capital, and part of that is having a very keen sense of what to do with it. When raising money at groupme and fundera, we always had a crystal clear idea of how much money we wanted to raise and why. Sometimes it was to be able to pay for some rapidly accelerating variable costs attributed to our fast growth; other times, we needed to invest in hiring people with different types of skills to build things like new mobile clients, or we wanted to scale a sales team after we had a basic sense of our payback periods and how we’d operationalize onboarding and ramp cycles. This wasn’t rocket science or even calculus, it was just a simple model we’d build in a spreadsheet. It demonstrated that we had some modicum of an idea as to what we’d spend money on, when we’d spend it, and why. And it’d be reflected in a basic pro forma and financial model that would grow in sophistication as we learned more about our business over time.

Some frameworks for this can be a simple comparison of what your company looks like today versus what it will look like in a future state due to this fundraise across a series of different attributes: team size and composition, customer or user growth, revenue growth, product features, releases and milestones or markets you’re live in, etc. Demonstrate and convey what will be different about your business when you raise the money. “We want to raise $10m to accomplish these things and have some buffer to invest in new initiatives opportunistically” is an infinitely better answer than “$10m feels right for us.” One shows you might be a thoughtful steward of capital, and the other is a total turn-off.

The process of doing this work isn’t super time consuming, and it’s remarkably important to help you think through just what it is you want to accomplish with money. If you’re asking for capital, at least have the wherewithal to answer these basic questions for yourself let alone investors. You’re selling a piece of your company. Be thoughtful about why you want to do that and why it will be worth it.

In Defense of Thin Wrappers

GroupMe first launched as an SMS-only application. All groups were assigned a unique phone number that you could add to your contacts as Family, College Friends, or Music Crew. You’d add members to the group with a series of SMS commands. When you sent a message to your group’s phone number, a text would be relayed to everyone else in the group. All of this was built using Twilio, which at that time had found a way to abstract away all the complexity of integrating with telecommunications infrastructure so application developers could focus on building great user experiences. We would have never existed without Twilio, but it also led to a real problem with our business: we paid for every single message we sent. The average size group was six people, so we paid when someone sent a message to the group phone number, and then we paid to relay that message five times to everyone else in the group. One message meant paying for it six times on average. We also paid every month to lease the group phone numbers.

This became an extremely expensive endeavor for a free service with no means of monetization. The product grew virally. For every group that was created, one user would go off and create their own, adding five new people to the network. Every group and message sent was a variable cost, and we were beholden to Twilio’s prices. We tried negotiating but could never get prices to a place that wouldn’t put us out of business. My co-founder Steve even proposed doing an equity swap with Twilio to align our respective fates, which was a wonderful idea but sadly rejected. Our only chance of survival was to raise enough money for VCs to subsidize our text messaging product while we found ways to drive down SMS costs and migrate our user base to an over-the-top mobile messaging application similar to WhatsApp.

To get off Twilio, we first had to understand how to get closer to telecommunications infrastructure, or “the metal,” as industry veterans called it. We hired consultants who ramped us up and helped us to identify two companies, Bandwidth and Level3, that Twilio was using to build their service on top of while they hammered out deals directly with telcos. These companies were not developer-friendly friendly, and we had to task Brandon Keene with the mission-critical responsibility of migrating GroupMe off Twilio and figuring out how to rebuild all of our SMS infrastructure while maintaining acceptable service levels for our users. We also had to play Bandwidth and Level3 off each other to negotiate bulk pricing that wouldn’t put us out of business and enable us to scale for the years ahead. We were in our early 20s and had no clue what we were doing.

We miraculously managed to cut a deal with Bandwidth, migrated off of Twilio, and bought ourselves enough time to wait for most of our users to switch to the native mobile app where we didn’t have to pay exorbitant SMS costs as the service scaled.

Lately, I have seen many companies that remind me of this GroupMe experience. They are building consumer-facing applications that sit on top of LLMs, primarily Open AI, and when they get some form of traction and grow, variable costs start skyrocketing. Similar to GroupMe, very quickly monthly costs ramp up to hundreds of thousands a month, but now it’s inference instead of SMS. Over time, these costs will come down for application developers. Market competition, open source, and locally hosted models will all make inference more affordable, but it’s unclear if we are operating on a timeframe of one year or five.

For most application developers, it’s not really an option to not use these models. Consumers are growing to expect the type of functionality and features they deliver. Once things start working, there will inevitably be some form of scaling and expensive inference costs that are meaningfully higher than what pre-LLM companies have experienced. Having to deal with these issues when you are growing is really hard. You effectively have to rebuild the engine of your machine mid-flight. It’s hard enough to improve your user experience continuously, hire people, do performance management, and run your company. Adding the capital sink of inference costs creates a whole new series of challenges.

This means it is incumbent upon founders to get ahead of this issue. Several things feel like best practices now:

Plan for using more than one model when you start, and begin to diversify at signs of inflecting. Being beholden to a singular LLM is likely a recipe for disaster. You have no leverage and are subject to pricing whims. Plan to be multi-model. This doesn’t mean starting with three integrations out the gate, it just means knowing who you’ll expand with and having an idea as to when you’ll do it and what the process will look like.

Learn how to route prompts to the right models. Not all models are created equal, and some are better at certain things than others. One of our portfolio companies has a wizard-like mastery of this. There are now many companies that act as an intermediary between applications and underlying LLMs, but I think if AI is a core part of your value proposition you need to master this yourself and can’t outsource it.

Find your Brandon. Someone inside your company needs to shoulder responsibility for owning your LLM strategy and executing the plan. Like all mission-critical things, accountability is everything.

Find a group of advisors who know how this all works. While LLMs feel reasonably new to a lot of people starting companies, there are experts out there who are excellent at helping assess which models best fit your needs, and understand how to think about competitive pricing and prompt routing. It’s probably a good idea to have a circle of 2-3 advisors who have some skin in the game that you can turn to with specific questions, both strategic and tactical.

Hone your business development chops. You’re going to be in a constant conversation with model providers asking for things: pricing, integrations, access to private betas, etc. These relationships matter. Invest in them.

Raise a little more money than you think you need as a buffer so you’re not always caught on your heels reacting to these costs. When things really work it means your costs will escalate faster than expected. Extra capital on your balance sheet may provide you with some peace of mind.

I’m sure there’s a lot more to add to this list, but it’s a start. This is likely the status quo for the next several years so it’s good for entrepreneurs to be aware of the current state of affairs and have a plan for it. Exciting times come with exciting challenges.

The Conversation

Yesterday, Matt and I published a post about vertically integrated and AI-first approaches to building companies that are transforming physical industries, specifically as it relates to accelerating the energy transition and mitigating the climate crisis. The article is a reflection of something that I've come to deeply appreciate about USV. We have conversations about topics that sometimes span a day, weeks, or months. Then, at some point, we are ready to share that conversation with the world and we synthesize it on the USV site.

My partner Andy said this phrase that I love: "USV is a conversation." I didn't understand it before I joined, but now I do. The conversation never ends. It may pause on a particular theme for a beat, but it picks back up and is in a constant state of evolution. Sometimes we've talked about something enough and the best way to move it forward is to invite the public to participate in it.

Another thing I now appreciate is how collaborative writing can be. After blogging here on my own for several years, it had been a while since I wrote articles with colleagues. Andy and I co-wrote a piece on healthcare. He has a beautiful way with words and an elegantly Socratic style. I learned a lot in the process of trying to meld our words together. The experience was unfamiliar and a little hard at first, but ultimately more fun than going it alone (and I think it yielded a better result, too). Similarly, Matt is exponentially more sophisticated than I am when it comes to everything climate related. I sent him a miserably shitty first draft that was a reflection of our internal conversations and emails around the topic, and he took the outline, evolved it, and filled it with substance.

This collaborative process is a continuation of the conversation, just on the page instead of aloud in the room. Sometimes it can feel hard to start it up, but once you're in the flow of it, it can take you to unexpected and important places.

It's Like This and Like That

One of the hallmark traits of what makes a consumer product weird is having difficulty describing the thing. That’s somewhat to be expected given the novelty of some products, particularly in this day and age when AI and crypto are enabling user experiences we’ve never seen before.

There have been several instances at USV lately where we’ve spoken with early-stage consumer companies and struggled to define what the product actually is. “It’s like a tool that makes everyone a creative wizard, but also a network where sharing things is a ton of fun!” “It’s a game, but also like a storytelling platform mixed with a group chat!” When we articulate these things to people the commonplace response is a look of bewilderment. I think that’s a good thing.

When we find ourselves using the Dre and Snoop refrain “It’s like this and like that and like this and a…” we know it’s time to take the product seriously and that the founder very well may be onto something special. An inability to succinctly articulate what a consumer experience does can actually be a positive signal. It means you’ll just have to try it out for yourself and see what it conjures.

Entrepreneur & Investor Paranoia

Every entrepreneur I know falls somewhere on the spectrum between paranoid to full-blown “the world is conspiring against me” paranoid. This is no surprise because only the paranoid survive. It creeps up everywhere: will a competitor lap me? Will a key employee leave? Will I lose that partnership? I just pitched an investor, are they going to share information with people I don’t want them to? A strategic is trying to acquire us, are they just fishing for information so they can directly compete? The list is infinite. No matter how well things are going, there is always something suspect in the air.

One area where paranoia always crept in for me was when investors asked whether I thought another company was competitive. When building GroupMe and Fundera my answer always defaulted to “Yes, of course.” At GroupMe if someone wanted to invest in a group-buying company, we’d block it because we had “Group” in our name and one day we might converge. If someone wanted to invest in a SMB insurance marketplace, we’d be insulted because we wanted to be the Everything Store for SMB financial products at some point in the next 5-100 years. My feeling was that investors made their bet on us, and anything even remotely adjacent or tangentially related was a blatant affront and off-limits. If they asked, I’d block it.

Now that I’m on the other side of the table, I think about this a lot.

When starting Fundera, I actively sought to work with investors who knew about our space. We were building a marketplace/brokerage for SMB loans, and we were relatively new to this world. If an investor had previous exposure to SMB lending it was a plus. Two of our first investors, First Round and Khosla Ventures, had invested in OnDeck Capital, a direct lender that would become an important partner and customer of ours. This was a positive signal to me - they believed in the space. Another one of our investors, QED, had invested in another SMB lender that became an early partner and customer of ours. In no way did I view this as a conflict, it was a positive differentiator.

But once we had an investor’s money, something changed for me. Whenever they’d try to make a new investment in a direct lending company (similar to the aforementioned ones), I’d attempt to block it, claiming it was competitive. This was irrational behavior. If it didn’t matter before, why would it matter now? I remember when one investor told me he made an investment in a direct lender without asking for my permission beforehand, I was absolutely livid. All I could see was red when he explained their new investment. (The company ended up becoming another important paying customer of ours, and the founder became a friend of mine whose next company I invested in.)

Reflecting on this, it seems hypocritical to feel this way and I’ve tried to piece together why that was the case. When the investment in Fundera (which actually felt like an investment in “me”) followed an investment in a direct lender, I felt validated, as if the investor made a previous mistake and was course-correcting by supporting us. But when the opposite happened, I felt betrayed, like the investor believed they made a mistake and we weren’t good enough. My feelings were real, but my assumptions were wrong. This was not an indictment of me as a person or a loss of belief in the potential of the company itself. It was an action reflective of a growing conviction in the space and a desire to deepen its financial investment in a theme they believed to be important. This was not supporting a competitor, it was strengthening a complement.

I think this will always be a sensitive topic and a tricky area to navigate. Some investors can be very helpful if they have exposure to a space and know the relevant players and industry dynamics. It’s easy to try to present making investments in an adjacent company as a logical and potentially beneficial thing to an entrepreneur, but investors should be empathetic and recognize that entrepreneurs have real feelings and are inherently paranoid about this. I don’t think investors should ask for permission, but they should always ask a Founder's opinion and factor it into their decision-making. At the end of the day, they’re only left with their reputation. For entrepreneurs, it’s important to internalize that these investment decisions are not a critique of them as a person or their business (unless the VC deliberately invests in a direct competitor, then they are asking to be written off). In fact, these actions can be a way of doubling down on your future. It’s hard to separate feelings and perception from intent. These situational dynamics are important and can get messy very quickly. There’s no substitute for putting yourself in the other person’s shoes.

Network Ownership and Profit Sharing

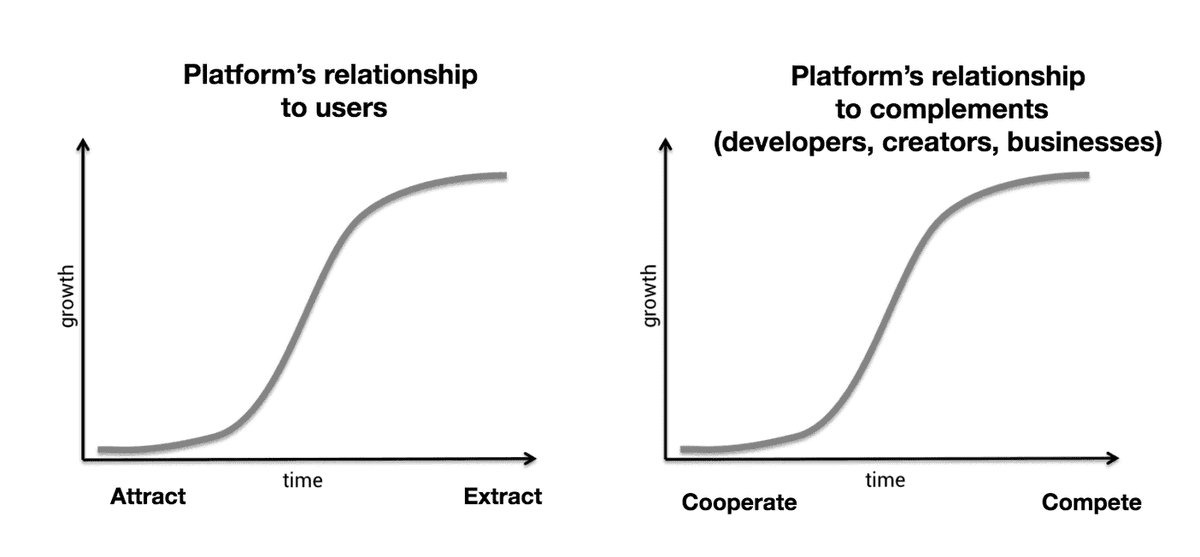

One of the things that I’ve always found compelling about web3 is the concept of user-owned networks. In web2, many networks were built on the backs of their users and developers. As the famous Chris Dixon example goes, networks and platforms do what they can to attract and cooperate with ecosystem participants early on. Then, as they hit the tops of their growth S curves, they pivot to value extraction and compete with the complementary applications that got them there in the first place. Web3 companies work to avoid this dynamic by giving the participants who help build and grow the network ownership in it. This is a powerful concept and an important ideal. It helps bootstrap networks and creates trust, guarantees, and aligns incentives.

One of the things I am interested in is web2 companies applying this web3 superpower to their domain. I am beginning to notice more of it in the wild. There are different flavors of this ranging from profit sharing to owning actual equity in a company. Bookshop.org gives 80% of its profit margin to independent bookstore in its network. It doesn’t have to do this, but it strengthens its network and creates preference in both buyers and sellers on the platform. When I buy books online I make sure to do it on Bookshop. YouTube has done an exceptional job nurturing its community of creators by famously awarding them 55% of the network's ad revenue.

With regards to equity, Nebula TV has taken a bold approach awarding the creators who produce content for the platform with 50% ownership. And while it may have been more of a marketing stunt than a thoughtful distribution of ownership, NuBank awarded $11.2m in stock to its depositors when it went public. I am sure there are plenty more instances of this happening, and I want to learn more about them.

I find these examples exciting because they are representative of a movement that distributes ownership of internet properties across a broader set of constituents. I hope that this type of practice becomes commonplace because the people who supply the products that power networks - whether books, content, money, or otherwise - should have incentive to stick around and participate in the upside. I don’t think all companies need to give away majority chunks of ownership to their network participants, but token gestures go a long way in establishing trust and preference.

I would like to see more of this, particularly companies that are able to harness this superpower and deliver it to users in a way that abstracts away the complexity of crypto rails. The concept is one of the most powerful things that can drive incentive alignment and value creation on the internet, and I think it can help web3 cross the mainstream chasm.

Agent Native Applications

AI is fundamentally changing the way we interact with technology. It has started with language and voice as an interface, and it will continue with the rise of agents. I think of agents as pieces of software that can do your bidding on the internet. They can navigate web, mobile, and desktop applications to accomplish tasks on your behalf. The recent Rabbit launch demonstrated to us what this can look like.

Agents are an inevitability. If mobile applications are remote controls for real life, agents are the universal remote. This begs the question of whether web2 companies that have built business models on top of pre-AI interaction models will adapt or even participate in the agent world. If services like Uber, Kayak, and Instacart generate a meaningful amount of revenue through advertisements and cross-selling products, will they want their application interfaces to be abstracted away by an agent? Are they okay with their customers never interacting directly with their applications and losing their eyeballs? Their incentive structure is at odds with agent proliferation. This is a potential innovator’s dilemma in the making.

New conversational interfaces made possible by AI will create a new category of “agent native” applications. Since agents will interact with them instead of end-users, these applications will be headless by nature. They may be entirely unknown to users and simply run in the background, happily playing their part in a series of chain reactions. These will be protocols that our agents call on in the world of bits and they will also bridge to atoms (eg ride-sharing, grocery delivery, etc.).

This is likely a scenario where AI and crypto will be two sides of the same coin. AI will create the need for agent-native headless applications, and web3 will step in to fill the void. Web3 applications and protocols can accommodate the new ways in which we will use technology (i.e. conversational and voice-centric interfaces with agents working for us) because they do not need to “own” end-to-end customer experiences unlike most web2 companies. They are happy to run in the background as composable job-doers. They don't need their brand names front and center because their tokenized business models, which are primarily straightforward and network usage-based, are positioned to thrive in this world, especially relative to their web2 counterparts.

I suspect we will see more and more of these “two sides of the same coin” scenarios emerge as AI and crypto continue to weave their way into our daily lives.

1,333

1,333